Mária Chilf

– born in 1966, Târgu Mureș, Romania. She studied at the Painting and Intermedia Department of the Hungarian University of Fine Arts. She graduated in painting and teaching in 1995. From 1997 to 1998 she studied at the Hochschule der Künste in Berlin. She has been teaching at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts since 2009, and is a senior lecturer since 2016. In 2019, she earned a DLA degree. Her practice unfolds in a variety of mediums (painting, graphics, photography, video, installation, community art projects) and connects seemingly distant concepts and phenomena through sensitive associations. Her work explores the functioning mechanisms of the human body and the soul, and is closely related to neo-conceptual art. Also calling on intuition and superimposing layers, she was initially building her pieces from organic materials, quoting biological illustrations. In the last 15 years, her attention has increasingly turned to the questions of the inner world of man, bringing to the fore topics such as trauma processing, healing and self-healing, as well as remembrance.

One of our basic activities in life is fighting for our identity: we try to define something that constantly changes. For me creation is about this quest. Thus the process of creating is also a dialogue between the world, the self and art. This is a dimension where these three elements are transforming to something else, if only temporarily. I see the purpose of art in this transformation; in forming and broadening the human consciousness. My aim is not to process a personal experience but I’m interested in a certain situation that allows me to build in, recreate and integrate my experiences as well.

An integral part of my artistic practice is revolving around basic, existential questions of humankind, such as death and trauma. I call the distance between me and my topic zoom in/zoom out, that can be the expression of scaling my understanding of being and reality. I often play with distance in time, I review important memories, I work with them conceptually, such as in my work Invisible Plan, or in the video Double/Trouble, where I experimented with various states of mind.

In my early works the self hides behind a symbolic, abstract objectivity. After an artistic silence caused by a tragedy in my private life in 2004 I tried to process the situation from the viewpoint of “immersing myself to the fullest”. My series Anything can happen to Teddy manifests this point of view1. Teddy, the protagonist of the series shaped the narrative frame for me, so I could talk about things that are otherwise taboos. The works are connected to my personal story but as parts of a fictional visual narrative they move apart from me as well.

I was always interested in human vulnerability and fragility of individual lives. Thus, in the beginning of my career it was also a trauma that prompted me to create objects and installations. Besides other organic materials, I often used paraffin that represents death, faith, conservation (as an experiment of manipulating time), and healing2.

Working with traumas can be grasped by the transitivity of the things we can control and those we cannot; and by the transition between personal experience and some kind of material. For me watercolour in the best possible way to visualize this relationship. This is the medium which holds me in the present moment, that can capture my attention during the process of creation and it also keeps me in motion and absorbs me. It simultaneously creates space for being focused and being open for uncertainties, possibilities, eventuality, coincidence and surprise. Yet I am able to control it. I am subordinated by the function of the material during the process. The material and my intention make me dynamic and that is what creates the whole procedure experiential3.

This way of expression is not exclusive: when I am interested in something, I try to find various media and I revolve around the possibilities of expression. A situation, a topic or a question comes up first and determines what I will work with. I am interested in sciences, not only art history and cultural history, but psychology too; and from natural sciences biology, which fascinated me for a long time. I like to detect things around me, but with a poetic and personal approach4. For example my works Denatured, Laboratory sample5 or Pigmentatio mundi6 are like that, or my series about environmental issues created in Bitterfeld7.

Research is a part of my practice, but its determining role and extent depends on the nature of the artwork in question. A conceptual piece of art requires another kind of research, such as the “completion”8 of the 1938 issue of the German dictionary called Duden with pages about Jewish religion and culture, or my DLA dissertation (2019) in which I am dealing with trauma.

Female perspective is strongly present in my work, but I don’t use striking elements, the attitude that is closest to me is not the feminist, political or activist point of view. Nevertheless, I worked on a community project dealing with issues connected to women in which I collaborated with seamstresses and I focused on their social situation9. As a private person I try to express my opinion and participate in public life. What I see around me, i.e. hate and nationalism are repelling for me, because I have experienced these living in the Ceausescu regime as an ethnic minority.

Being a member of the Hungarian population located outside current-day Hungary, a “second-hand identity” followed me in my life since my childhood. Living in Târgu Mureș I was always longing for someplace else. Now I know that the provincialism I was suffering from is typical for the whole Eastern European region.

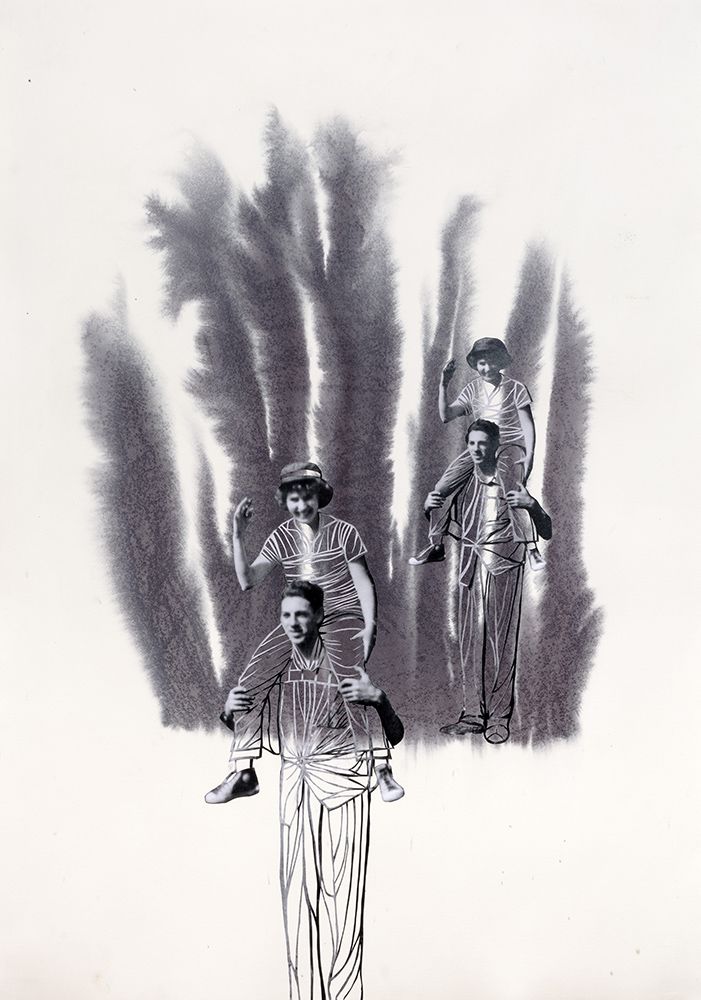

My experiences as a member of a minority and my investigations about my family’s memory inspired artworks such as the Transitory objects project. The suddenly found Hungarian court dress of my grandmother recalled a chain of stories from the history of my family and prompted me to dig deeper in the topic. One part of this project is the video called Trans-national10 in which I am wearing my grandmother’s dress, walking with a suitcase and grocery bags from the door of my apartment in Pest to the Buda side through symbolic sites of the city, and then back again. The body crossing the bridge became a bridge itself as well between past and present, its ancestor and itself, Transylvania and Hungary and between departures and arrivals. However the baggages make the whole marching, ironic so it alludes to the issues of immigration, homeland and the faith of women as well. The series Family Album (2014-2018)11 is a continuation of this project, consisting of cut out photos and collages. I recreated some copies of family photos by cutting them out. By doing so I was also processing: the aggressive move of cutting made me able to redraw the figures of my ancestors, to make them mine and to transform them into patterns.

The process of “redrawing” found family photos, as a trace of memory, has been exciting for me ever since. I follow the lines, I create lines, I find threads towards the distance of photographs so the images become my own, personalized documents12.

The statement was written in collaboration with art historian Kata Balázs (2020).

1Image: Mária Chilf, In therapy (Anything can happen to Teddy), 2004, watercolour, 30 x 40 cm. Courtesy of the artist and VILTIN Gallery, Budapest.2Image: Mária Chilf, Untitled II, 1994, installation: plastic tube, duct tape, flour, clay, wood, paraffin, metal, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and VILTIN Gallery, Budapest.

3Image: Mária Chilf, Background Horizon, 2009-2010, stain, paper, 70x100 cm. Courtesy of the artist and VILTIN Gallery, Budapest.

4Image: Mária Chilf, Untitled VI, 1997, watercolour, ink, paper, 50 x 70 cm. Courtesy of the artist and VILTIN Gallery, Budapest.

5Image: Mária Chilf, Laboratory Sample, 1998, installation: plastic tube, glass, pasta, taxidermy (white mouse), metal, 350 x 180 x 70 cm. Courtesy of the artist and VILTIN Gallery, Budapest.

6Image: Mária Chilf, Pigmentatio mundi, 1999, installation: C-print, watercolours, glass dissection dish, rubber gloves, test tube, glass plate, flyers, table, chairs, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and VILTIN Gallery, Budapest.

7Image: Mária Chilf, from the Burdened Landscapes series, 2003, stain, ink, paper, 70 x 100 cm. Courtesy of the artist and VILTIN Gallery, Budapest.

8Image: Mária Chilf, Duden, improved, extended edition, 2014, digital print, paper, 30 x 40 cm. Courtesy of the artist and VILTIN Gallery, Budapest.

9Image: Mária Chilf, Private pattern, Mezőszemere, 2010, embroidery, photography, diary, canvas, wood, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and VILTIN Gallery, Budapest.

10Image: Mária Chilf, Trans-national, 2014, video. Courtesy of the artist and VILTIN Gallery, Budapest.

11Image: Mária Chilf, Tale (from the series Family Album), 2015, stain, cut out photograph on paper, 40 x 30 cm. Courtesy of the artist and VILTIN Gallery, Budapest.

12Image: Mária Chilf, Many many moments, 2019, stain, photo cut-outs on paper, 100 x 70 cm. Courtesy of the artist and VILTIN Gallery, Budapest.

szül. 1966, Marosvásárhely/Târgu Mureș, Románia, képzőművész. A Magyar Képzőművészeti Egyetem festő- és intermédia szakán tanult. Festő szakon és tanárszakon 1995-ben diplomázott. 1997-1998 között Hochschule der Künste-ben tanult Berlinben. 2009 óta oktat a Magyar Képzőművészeti Egyetemen, 2016 óta osztályvezető tanárként. 2019-ben DLA fokozatot szerzett. Különféle médiumokban (festészet, grafika, fotó, videó, installáció, közösségi művészeti projektek) készült alkotásai érzékeny asszociációkon keresztül kapcsolnak össze látszólag távoli fogalmakat, jelenségeket. Az emberi test és a lélek működésének mechanizmusait kutató, a neokonceptuális művészettel szoros kapcsolatban álló, de az intuícióra, egymásra rakódó rétegekre is épülő munkái kezdetben organikus anyagokból építkeztek, biológiai illusztrációkat idéztek. Az utóbbi 15 évben figyelme egyre inkább az ember belső világának kérdései felé fordult és a traumafeldolgozás, a gyógyítás és öngyógyítás, valamint az emlékezet került érdeklődése előterébe.

Életünk alapfoglalatossága az a küzdelem, amit identitásunkért folytatunk: valami állandóan változásban levőt próbálunk meghatározni. Az alkotás számomra erről a keresésről szól. Az alkotási folyamat ugyanakkor párbeszéd a világ, a művészet, valamint az én között is. Ez egy olyan dimenzió, amelyben mindhárom, még ha csak átmenetileg is, valami mássá alakulhat. Ebben látom a művészet feladatát: a transzformációban, az emberi tudatosság alakításában, tágításában. Nem a személyes élmény feldolgozása a célom, hanem az adott helyzet érdekel – amelynek mentén a személyes tapasztalataimmal, élményeimmel dolgozom (beépítem, összegyúrom, átformázom őket).

Alkotói tevékenységemnek szerves része az alapvető, embert érintő, egzisztenciális kérdések, így a halállal, traumákkal történő foglalkozás. Témám és személyes én-em között húzódó distancia pulzálását zoom in/zoom out-nak nevezem, amely a lét- vagy valóságértelmezés kalibrálásának a kifejezője lehet. Sokszor játszom az idő távolságával is, számba veszem a meghatározó emlékeket, és konceptuálisan dolgozom velük (Láthatatlan alaprajz), más esetlben azonban a tudatállapotokat vizsgálom, például a Double/Trouble c. videoalkotásban.

Korai alkotásaim esetében szimbolikus, elvonatkoztató tárgyiasság mögé bújik az én, azonban egy magánéleti tragédia (2004) okozta törést követő „alkotói csend” után a „mélyen elmerülni” attitűdöz választottam, és evvel igyekeztem feldolgozni a helyzetet. Erről tanúskodik a Brumival bármi megtörténhet c. sorozat1. Brumi, a sorozat főszereplő-(mese)figurája narratív keretet biztosított számomra, mely segítségével ki lehetett mondani dolgokat, amikről nem lehet beszélni. A művek kapcsolódnak a személyes történetemhez, de egy fiktív vizuális narratíva részeiként el is távolodnak tőlem. Mindig érdekelt az ember sérülékenysége, és az egyéni életek törékenysége. Már pályám kezdetén is egy trauma hatására történt, hogy tárgykészítéssel, installációkkal kezdtem foglalkozni. Az organikus anyagok mellett gyakran használtam paraffint, amely jelentése szimbolikusan a halál, az elmúlás, a konzerválás (mint az idő manipulálására tett kísérlet) és a gyógyítás folyamataihoz is kapcsolható2.

A traumákkal való munka a kontrollálható és a nem kontrollálható tranzitivitásaként ragadható meg, azonban a személyes élmény valamilyen anyaggá való átfordulásaként is tekink rá. Ezt a viszonyt az akvarell tudja a leginkább megjeleníteni számomra, mint a “jelenben levés” médiuma és közege, amely mozgásban és nyitottan tart, és leköti a figyelmemet. Egyszerre ad teret a fókuszáltságnak és a bizonytalanságnak, a lehetőségeknek és az esetlegességnek, a véletlennek és a meglepetéseknek, miközben mégis az irányítás érzetét adja. Munkám során az anyagnak rendelődöm alá, és az, ahogyan ez és az intencióm dinamizál, teszi élményszerűvé a műveletet3.

Kifejezésmódom azonban nem kizárólagos: ha valami foglalkoztat, ahhoz különféle médiumokat keresek, és körbejárom a kifejezési lehetőségeiket. Egy helyzet, téma, kérdés fogalmazódik meg elsőként, majd ez határozza meg, hogy mivel fogok dolgozni. Érdekelnek a tudományok, nemcsak a művészettörténet, kultúrtörténet, de a pszichológia is; a természettudományok közül a biológia sokáig egyenesen lenyűgözött. Szeretem detektálni a dolgokat magam körül, azonban költői és személyes eszközökkel4. A Denaturált, a Laborminta5 vagy a Pigmentatio mundi6 c. alkotásom is ilyen, vagy a környezeti problémákra reflektáló bitterfeldi sorozatom7. A kutatás a tevékenységem egyik eszköze, de szükségessége és mértéke az adott alkotás jellegétől függ elsősorban. Egy konceptuális mű, mint a Duden Bildwörtenbuch 1938-as kiadásának a zsidó vallásra és kultúrára vonatkozó lapokkal való „kiegészítése”8, vagy kifejezetten a traumával foglalkozó doktori disszertációm (2019) tényleges, alkotást megelőző kutatást igényeltek.

A női perspektíva megtalálható a munkáimban, de nem használok plakatív megoldásokat, nem a politizáló feminista vagy aktivista attitűd az, ami a számomra a legjobban megfelel. Ugyanakkor van olyan női témák iránt nyitott közösségi projektem, ahol (hivatásos varrónőkkel dolgoztam) a nők szociális helyzetével foglalkoztam9. Magánemberként igyekszem véleményt nyilvánítani és részt venni a közéletben. A gyűlölködés és nacionalizmus azért taszít annyira, mert kisebbségiként a Ceaușescu-rendszerben már átélt, személyes élményem van erről.

Határon túli magyarként az általam “second-hand”-nek titulált identitás gyerekkorom óta kísér, ezért nagyon erős volt bennem az elvágyódás. Most már tudom, hogy az a provincializmus, amitől szenvedtem, az egész térségre jellemző.

A kisebbségi lét tapasztalatai, illetve a családom emlékezetével foglalkozó vizsgálataim vezettek olyan munkákhoz, mint az Átmeneti tárgyak című projekt. A nagymamám váratlanul előkerült díszmagyar ruhája történetek láncolatát hívta elő, általam nem ismert és elhallgatott családtörténet utáni kutatásra sarkallt. A mű részét képező Transz-nacional10 című videó azt dokumentálja, amint a nagymamám ruhájába bújva bőrönddel, bevásárlószatyrokkal bandukolok a pesti lakásom kapujától szimbolikus helyszíneken keresztül Budára, majd vissza. A hídon áthaladó test maga is híddá vált múlt és jelen, felmenője és önmaga, Erdély és Magyarország, elindulások és megérkezések között. A csomagok ugyanakkor ironikussá is teszik ezt a vonulást, amely így az emigráció, a hon, de a női sors kérdésköreit is érintheti. E mű részeként és folytatásaként értelmezhető a Családi album című sorozat (2014–2018)11, amely fotókivágásokból és kollázsokból áll. Kivágással, áttöréssel „átrajzoltam” néhány családi fotóról készült másolatot. A megmunkálás révén a múlthoz való személyes viszonyom is változott: a vágás erőszakosságával újrarajzoltam őseim figuráit, magamévá tettem, kisajátítottam, új mintázatba “írtam át” őket.

A talált családi fotónak – mint emléknyomnak – az „átrajzolása” azóta is foglalkoztat. Követem a vonalakat, vonalakat alakítok, szálakat találok a fotográfiák távolságához, és így a képek a saját megszemélyesített dokumentumaimmá válnak12.

A statement Balázs Kata művészettörténésszel együttműködésben született (2020).

1Kép: Chilf Mária, Terápiában (Brumival bármi megtörténhet), 2004, akvarell, 30x40 cm. A művész és a VILTIN galéria jóvoltából.2Kép: Chilf Mária, Cím nélkül II., 1994, installáció: műanyag cső, ragasztószalag, liszt, agyag, fa, paraffin, vas, változó méret. A művész és a VILTIN galéria jóvoltából.

3Kép: Chilf Mária, Háttérhorizont, 2009-2010, pác, papír, 70 x 100 cm. A művész és a VILTIN galéria jóvoltából

4Kép: Chilf Mária, Cím nélkül VI., 1997, akvarell, tus, papír, 50 x 70 cm. A művész és a VILTIN galéria jóvoltából.

5Kép: Chilf Mária, Laborminta, 1998, installáció: műanyagcső, üveg, tészta, állatpreparátum (fehér egér), fém, 350 x 180 x 70 cm. A művész és a VILTIN galéria jóvoltából.

6Kép: Chilf Mária, Pigmentatio mundi, 1999, installáció: C-print, akvarellek, preparátumos üveg, gumikesztyű, kémcső, üveglap, szórólapok, asztal, székek, változó méretek. A művész és a VILTIN galéria jóvoltából.

7Kép: Chilf Mária, A Terhelt helyek-sorozatból, 2003, pác, tus, papír, 70 x 100 cm. A művész és a VILTIN galéria jóvoltából.

8Kép: Chilf Mária, Duden, javított, bővített kiadás, 2014, digitális nyomat, papír, 30x40 cm. A művész és a VILTIN galéria jóvoltából.

9Kép: Chilf Mária, Saját mintás, Mezőszemere, 2010, hímzés, fotó, napló, vászon, fa, változó méretek. A művész és a VILTIN galéria jóvoltából.

10Kép: Chilf Mária, Transz-nacional, 2014, videó. A művész és a VILTIN galéria jóvoltából.

11Kép: Chilf Mária, Mese (a Családi album-sorozatból), 2015, pác, fotókivágás papíron, 40 x 30 cm. A művész és a VILTIN galéria jóvoltából.

12Kép: Chilf Mária, Sok-sok pillanat, 2019, pác, fotókivágás papíron, 100 x 70 cm. A művész és a VILTIN galéria jóvoltából.