Yuliia Danylevska / Юлія Данилевська

– born in 1986 in Kherson. A multidisciplinary artist, she works with graphics, painting, video, and embroidery. She has had solo exhibitions at the Stanislav Voliazlovsky Museum of Modern Art in Kherson. She is a participant in the art group Herart and took part in the First Kherson Feminale.

I spent 8 months in the occupied Kherson, from the beginning of the occupation on March 1, 2022, until its end. I cannot say that the occupation fundamentally changed me as an artist. I was always sensitive to social processes, so I continued on the path I had chosen. As an artist, I work “intuitively”: I notice the “gaps” that abound in reality and reveal them in my works. Sometimes there is a temporal and spatial distance between the subject of research and the artist’s practice, but I directly and instantly read what is happening around me. Lately, it feels like I am living in the pages of a history textbook.

I draw domestic scenes from life during the war and occupation on tiles. I metaphorically embody new images that arose after the full-scale invasion or deconstruct old ones that previously had a steadfast connotation in the collective subconscious.

I have artworks on tiles depicting random mistakes made when we are in a hurry, anxious, or tired: lighting a cigarette from the wrong end; a person hastily buttoning up a shirt misses a button. Through these small details, where the “devil” hides, the subconscious reminds of itself. In another work, a man wears his female companion’s jacket. By swapping elements in a situation where a gentleman might lend his jacket to a lady, I normalize an action that might seem funny or even unacceptable in society.

I use folklore, slang, and idiomatic expressions common in the former USSR, as well as literalism as a method: I have a tile with a rat with bird wings flying and holding a twig in its paws. This work was inspired by the phrase that pigeons are winged rats, and the “peacekeeping” rhetoric of the Russians who came to our land with war. If they can be “doves of peace,” only in such a way.

During the occupation, Kherson was getting rid of its provinciality: the city “matured” and gained agency before our eyes, albeit forcibly. Communities rallied, fought for their rights and freedoms. However, it was a “secret” process that occurred against the backdrop of total external loss of independence. Kherson residents gained extreme survival experience, unreal and incomprehensible to residents of unoccupied Ukraine: daily acquisition of food, water, secret volunteering, spying for the Armed Forces of Ukraine. This was a spontaneous rebuilding of civil society in complete isolation from the world. Every day back then was perceived as the last one, especially at the beginning and end of the occupation.

I consider myself lucky to have witnessed and participated in this process. Despite the fear and difficulties, I do not regret staying in the occupied city. I want to be understood correctly, I do not suffer from Stockholm syndrome, my dream is for this war to finally end with our victory. But I have gained experience that is now always with me. I constantly compare what my life was like before the war, during the occupation, in liberated Kherson (under daily shelling), and what it is now – in relatively peaceful Mykolaiv. Honestly, it’s the worst now. Here, in Mykolaiv, nothing happens. I feel like I’m not living, just waiting and killing time, though I continue to paint.

During the occupation, I closely communicated with the local artistic community. We were confused but tried to continue creating secretly. We gathered in the studio of the artist Oleksandr Zhukovsky, shared information, rumors, and impressions of what was happening. After the invasion and occupation, just seeing and physically feeling my friends and colleagues was incredible. Perhaps it has already been forgotten against the background of other Russian crimes, but the beginning of the occupation of Kherson was bloody: on the night of March 1, at least 36 men from the territorial defense were killed, the Russians shelled several cars and houses with tanks and firearms, killing several civilians. We hid our activities from the Russians because the occupiers were desperately looking for people involved in any form of art, members of associations or organizations, or those developing creative industries. They offered such people to collaborate and lead positions in newly created ministries and cultural institutions that were taken over. None of us wanted such a fate. We continued to meet during the time in between standing in lines at pharmacies and stores, sometimes going to the artist Viacheslav Mashnytsky1 after rallies, and when it warmed up, we crossed the Dnipro to his dacha.

Now friends have scattered to different cities. Both Kherson and the neighboring Mykolaiv are empty. I try to make up for the lack of communication with like-minded people at residencies and short trips to other cities, continuing to paint and be my own art environment. It reminds me of playing with dolls alone in childhood after friends left, and you’ll only see them on weekends.

The text is written in collaboration with Oksana Briukhovetska (2024).

1The figure of Mashnytsky is pivotal for the development of contemporary art in Kherson, as in 2002, he founded the Museum of Contemporary Art in his residence, which now bears the name of Stanislav Voliazlovsky, and also established a charitable foundation for the naïve artist Polina Rayko. Before the war, the museum was bustling with life: exhibitions, play readings, and book presentations. Two of my personal exhibitions took place right in his apartment-museum. Unfortunately, a month before the de-occupation, Slava Mashnytsky disappeared, and we still do not know where he is or what happened to him.2Image: Yuliia Danylеvska, Aberration-1, 15x15 cm, tile, markers, 13.08.17. Courtesy of the artist.

3Image: Yuliia Danylеvska, Aberration-2, 15x15 cm, tile, markers, 03.09.20. Courtesy of the artist.

4Image: Yuliia Danylеvska, In the Dairy Section, 15x15 cm, tile, markers, 30.07.17. Courtesy of the artist.

5Image: Yuliia Danylеvska, Dove of Peace, 15x15 cm, tile, markers, 31.07.21. Courtesy of the artist.

6Image: Yuliia Danylеvska, Skin, 33x24 cm, gouache, paper, 14.02.23. (series "Negative Thinking"). Courtesy of the artist.

7Image: Yuliia Danylеvska, Olives, 34x25 cm, gouache, paper, 25.02.23. (series "Negative Thinking"). Courtesy of the artist.

8Image: Yuliia Danylеvska, Zakarpatsky Border Guards, 49x54 cm, gouache, paper, 18.06.23. (series "Negative Thinking"). Courtesy of the artist.

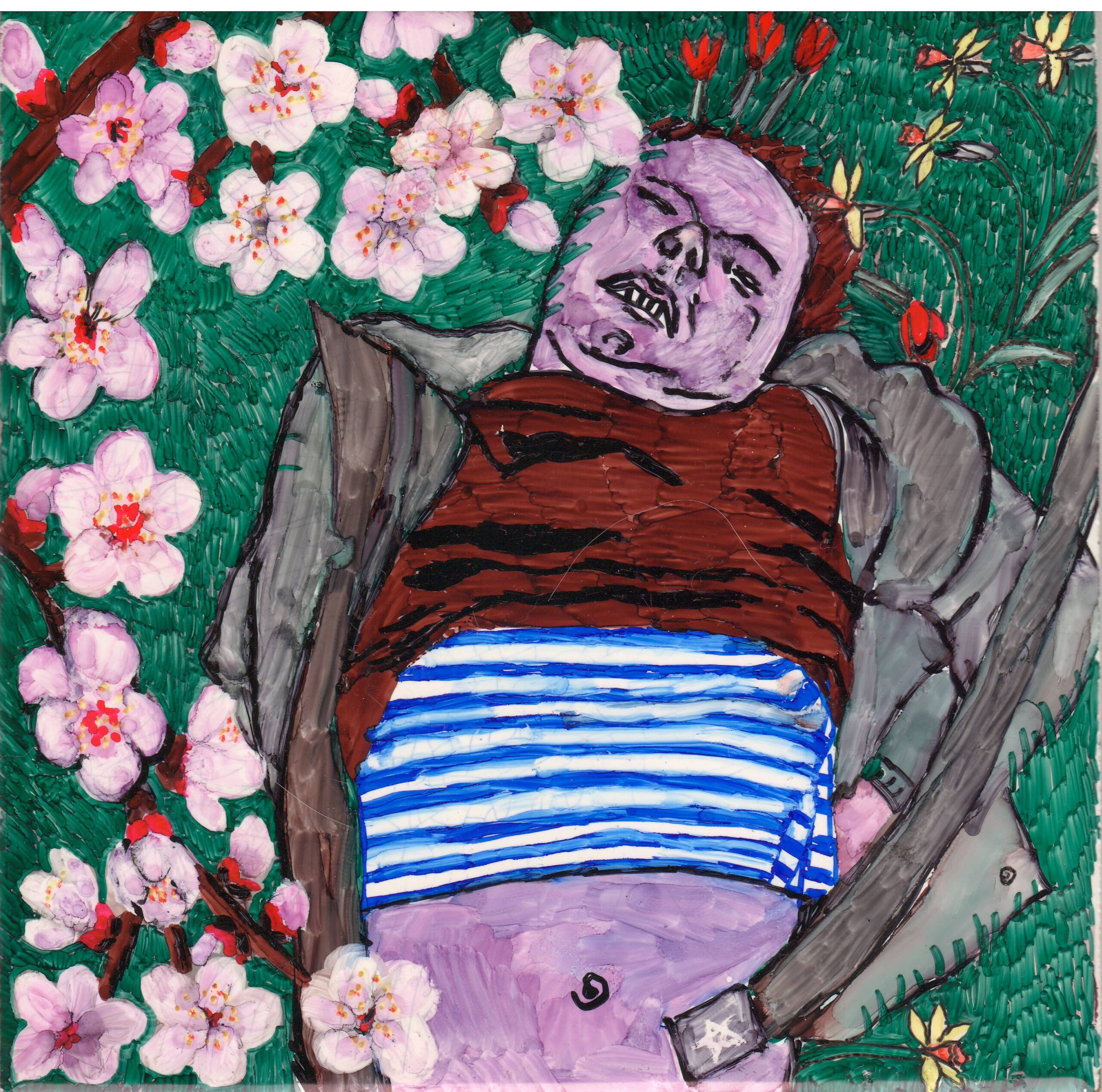

9Image: Yuliia Danylеvska, Dance, 49x59 cm, gouache, paper, 29.06.23. (series "Negative Thinking"). Courtesy of the artist.

10Image: Yuliia Danylеvska, Snow Gatherers, 15x15 cm, tile, markers, 18.03.22. (works created during the occupation). Courtesy of the artist.

11Image: Yuliia Danylеvska, Trophy, 15x15 cm, tile, markers, 06.04.22. (works created during the occupation). Courtesy of the artist.

12Image: Yuliia Danylеvska, Rule of 2 Walls, 15x15 cm, tile, markers, 28.03.22. (works created during the occupation). Courtesy of the artist.

13Image: Yuliia Danylеvska, Paratrooper, 15x15 cm, tile, markers, 15.04.22. (works created during the occupation). Courtesy of the artist.

— Народилася в 1986 році в Херсоні. Мультидисциплінарна художниця, працює з графікою, живописом, відео та вишивкою. Мала персональні виставки робіт в Музеї сучасного мистецтва Херсона імені Станіслава Волязловського. Учасниця мистецької групи Herart, брала участь в Першій Херсонській Feminale.

Я пробула в окупованому Херсоні 8 місяців, від початку окупації 1 березня 2022 року і до її кінця. Не можу сказати, що окупація докорінно змінила мене як художницю. Я й раніше була чутливою до суспільних процесів, тож ішла далі второваною стежкою. Як художниця, я працюю «інтуїтивно»: підмічаю «прогалини», якими рясніє реальність, і оприявнюю їх у роботах. Іноді між предметом дослідження і практикою художника пролягає часова й просторова відстань, я ж напряму і миттєво зчитую те, що відбувається навколо. Останнім часом здається, що я живу на сторінках підручника історії.

Я малюю на кахлях побутові сцени з життя під час війни і окупації. Метафорично втілюю нові образи, які виникли після повномасштабного вторгнення або деконструюю старі, які раніше мали непохитну конотацію у колективному підсвідомому.

У мене є роботи на плитці, на яких зображені випадкові хибні дії, коли квапимося, хвилюємося або втомлені: я підкурюю цигарку не з того боку; людина поспіхом застібаючи сорочку пропустила один ґудзик. Через ці дрібниці, в яких ховається «диявол», підсвідоме нагадує про себе. В іншій роботі чоловік одягнув жакет своєї супутниці. Помінявши місцями доданки в ситуації, коли чоловік по-джентельменськи позичає дівчині свій піджак, я нормалізую дію, яка може здаватися смішною чи навіть неприпустимою в суспільстві.

Я використовую фольклор, сленг і крилаті вирази, які поширені на теренах колишнього СРСР, а також буквалізм як метод: у мене є кахля, де намальований пацюк з пташиними крилами, він летить і тримає гілочку в лапках. На цю роботу мене надихнула фраза, що голуби це крилаті щури, а також “миротворча” риторика росіян, які прийшли на нашу землю з війною. Якщо вони можуть бути “голубами миру”, то тільки такими.

Під час окупації Херсон позбувався провінційності: місто «дорослішало» і набувало суб’єктності на очах, хай і вимушено. Спільноти гуртувалися, боролися за свої права та свободи. Проте це був «таємний» процес, що відбувався на фоні зовнішньої тотальної втрати незалежності. Херсонці щодня набували екстремального досвіду виживання, нереального і малозрозумілого для жителів неокупованої України: щоденне добування їжі, води, таємне волонтерство, шпигунство на користь ЗСУ. Це було спонтанне будівництво наново громадянського суспільства у повній ізольованості від світу. Кожен день тоді сприймався як останній, особливо на початку і в кінці окупації.

Я вважаю, що мені пощастило стати свідком та учасницею цього процесу. Попри страх і труднощі не шкодую, що залишалася в окупованому місті. Хочу, щоб мене вірно зрозуміли, я не страждаю на Стокгольмський синдром, моя мрія, щоб ця війна нарешті закінчилася нашою перемогою. Але я набула досвіду, який тепер завжди зі мною. Я весь час порівнюю, яким моє життя було до війни, яким під час окупації, яким у звільненому Херсоні (під щоденними обстрілами) і яким є тепер – у порівняно мирному Миколаєві. Якщо чесно, найгірше тепер. Тут, у Миколаєві, нічого не відбувається. Я наче й не живу, а чогось чекаю і вбиваю час, хоч і продовжую малювати.

Під час окупації я тісно спілкувалася з місцевою мистецькою спільнотою. Ми були розгублені, але намагалися й далі таємно займатися творчістю. Збиралися у майстерні художника Олександра Жуковського, ділилися інформацією, чутками, враженнями від того, що відбувається. Після вторгнення та окупації просто бачити та фізично відчувати своїх друзів та колег було чимось неймовірним. Можливо, це вже й забулося на фоні інших злочинів росіян, але початок окупації Херсона був кривавим: в ніч на 1 березня загинуло щонайменше 36 чоловіків із тероборони, росіяни обстріляли з танків та стрілецької зброї кілька машин і садиб, вбивши кількох мирних жителів. Ми приховували свою діяльність від росіян, бо окупанти відчайдушно шукали людей, які займалися будь-яким мистецтвом, були членами спілок та організацій або розвивали креативні індустрії. Вони пропонували таким людям співпрацювати і очолювати посади у новостворених міністерствах та захоплених закладах культури. Ніхто з нас не хотів такої долі. Ми продовжували зустрічатися в проміжках між стоянням у чергах в аптеки та магазини, інколи заходили до художника В’ячеслава Машницького1 після мітингів, а коли потепліло, перетинали Дніпро і приїжджали до нього на дачу.

Наразі друзі роз’їхалися по різних містах. Спорожніли і Херсон, і сусідній Миколаїв. Я намагаюсь надолужити відсутність спілкування з однодумцями на резиденціях і коротких подорожах в інші міста, продовжуючи малювати і бути сама собі арт середовищем. Це нагадує як в дитинстві гралася ляльками наодинці після того, як друзі пішли і ви побачитеся тільки на вихідних.

Текст створений у співпраці з Оксаною Брюховецькою (2024).

1Постать Машницького для розвитку сучасного мистецтва Херсона визначальна, адже у 2002 у своєму помешканні він заснував Музей сучасного мистецтва, який тепер носить ім'я Станіслава Волязловського, а також благодійний фонд художниці-наївістки Поліни Райко. До війни у музеї вирувало життя: виставки, читки п’єс та презентації книг. Дві мої персональні виставки відбулися саме в його квартирі-музеї. На жаль за місяць до деокупації Слава Машницький зник і ми досі не знаємо, де він і що з ним сталося.2Зображення: Юлія Данилевська, Аберація-1, 15х15 см, плитка, маркери, 13.08.17. Надано художницею.

3Зображення: Юлія Данилевська, Аберація-2, 15х15 см, плитка, маркери,03.09.20. Надано художницею.

4Зображення: Юлія Данилевська, В молочному відділі, 15х15 см, плитка, маркери, 30.07.17. Надано художницею.

5Зображення: Юлія Данилевська, Голуб миру, 15х15 см, плитка, маркери, 31.07.21. Надано художницею.

6Зображення: Юлія Данилевська, Шкура, 33x24 см, гуаш, папір, 14.02.23. (серія «Негативне мислення»). Надано художницею.

7Зображення: Юлія Данилевська, Оливки, 34x25 см, гуаш, папір, 25.02.23. (серія «Негативне мислення»). Надано художницею.

8Зображення: Юлія Данилевська, Закарпатські прикордонники, 49х54 см, гуаш, папір, 18.06.23. (серія «Негативне мислення»). Надано художницею.

9Зображення: Юлія Данилевська, Танець, 49х59 cм, гуаш, папір, 29.06.23. (серія «Негативне мислення»). Надано художницею.

10Зображення: Юлія Данилевська, Збирачі снігу, 15х15 см, плитка, маркери, 18.03.22. (роботи створені під час окупації). Надано художницею.

11Зображення: Юлія Данилевська, Трофей, 15х15 см, плитка, маркери, 06.04.22. (роботи створені під час окупації). Надано художницею.

12Зображення: Юлія Данилевська, Правило 2 стін, 15х15 см, плитка, маркери, 28.03.22. (роботи створені під час окупації). Надано художницею.

13Зображення: Юлія Данилевська, Десантник, 15х15 см, плитка, маркери, 15.04.22. (роботи створені під час окупації). Надано художницею.