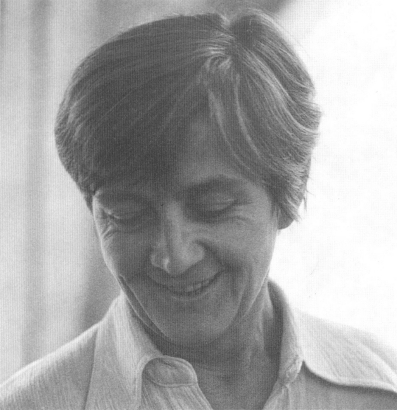

– born in 1923, died in 2004 – was a Czech painter and a textile artist. She graduated from the Studio of Textile Creation of Antonín Kybal at the Academy of Arts, Architecture, and Design in Prague in 1948. After graduation, she worked at the Institute of Housing and Clothing Culture, where she created abstract patterns for textile and much more. From the 1960s, she devotes herself to her own independent artistic practice.

Olga Karlíková came from a family of traders. Even though her father Leopold Karlík owned the international shipping company Karlík a spol., her journey to art-making was not that long. She was a granddaughter of Antonín Zajíček, a constructer who designed several houses in Kroměříž. She entered the art scene after graduating from the French lyceum in Prague as she enrolled into the graphics school Officina Pragensis (1939-1940). She spent the years of the Second World War in the studio of Antonín Strnadel at the School of Applied Arts in Prague (1942-1945), which gained the status of a university after the war. Karlíková continued her studies at what had become the Academy of Arts, Architecture, and Design, joining the Studio of Textile Creation of Antonín Kybal (1945-1948). For Karlíková, Kybal’s studio was probably a path towards a free artistic practice — despite the fact that it was a studio of applied arts. And perhaps this is exactly where Karlíková’s path in the direction of the minimalist lines she reached in her drawings opened up. During the 1950s and 1960s, she worked in Textile Creation to later join the Institute of Housing and Clothing Culture. She presented her work at an exhibition in 1959 at the Czechoslovak Writer’s Gallery.

Textile creation of the 1950s and 1960s was one of the free domains of art, which was being influenced by the abstract tendencies that were emerging in the West. The textile artists thus had the opportunity to escape the forced realism of the political ideology of the time through the possibilities within the framework of applied arts. It was the technology of the new materials that devised and welcomed new approaches to the decor since these modern fabrics, with their imperceptible weaving and fine structure, truly needed further processing. Abstract patterns thus became a suitable addition, as they did not work with one continuous pattern, but with spots that could be applied in a more flexible manner to the surface of the fabric. In her textile designs, Karlíková was employing this abstract expressiveness, although, in her independent work, she still resorted to the depicting conceptions of Václav Bartovský, who led a painting course at ÚBOK1. However, Johana Lomová points out that designating her textile designs as authorial gestures would be problematic. Considering the manner in which ÚBOK operated, it was more of a collective work, which manifested itself in the details of the result, such as colour tuning of textiles234.

Karlíková began to devote herself to her independent work gradually, at first only after work and on Sundays. She used to paint with a group of students that gathered around Václav Bartovský’s en plein air around Litoměřice5. She was completely immersed in her own paintings. Karlíková gradually deviated from landscape painting and began to create her first frottage. Even though she abandoned the depiction of landscape in the traditional sense in the early 1960s, it was still a tool for thinking about shape and space. Thus her interest in nature never disappeared from her work. On the contrary, nature remained present in her thinking. “A tree is a living organism firmly attached to the earth. Its own movement takes place in its inside. It is invisible, but we can sense its power. The tree grows and matures, it trembles and bends with the wind. It lives in symbiosis with the birds. Its crown is embroidered with their flight: it is their refuge that sustains them, and in turn, they spread its seeds far throughout the surroundings. Trees live to be the longest of age of all living organisms, I’d rather say beings. They are vulnerable, fragile and defenceless, but also resilient. The old linden trees in the alley, which had been cut down and whose stumps had been destroyed in a mill, sprouted once again from the roots the following year. Trees have their own stories, which are often very sad. I return to some in my area, sometimes after a long time of wandering around and experiencing my confusion. They are here at their places, some badly injured, with dying branches, but with burgeoning buds, golden leaves or bare crowns. The trees convince me of the order of nature. It’s a large topic and I don’t know whether I am enough.”6

Karlíková’s structural abstraction soon leaned towards the acoustics of nature, as she recorded the sounds of birds7, frogs and, according to the record, also whales8. Her work thus began to oscillate between entries of text, notation and visual sign. Her visual scores of nature resembled the calligraphic poems in Asian art, which she explicitly referenced in a way through adjustment. She once described her distinctive concept: “What is a poem, what is poetry. Perhaps a flash of light, a sharp look that is also fragile, revealing a secret, sinking into the abyssal depths, floating towards the dizzying heights. A few words, lines or spots often reveal more than excessive talking.”9 Her original interest in landscape painting was abstracted into the study of water level rhythm10, space with gusts of wind and other similar abstractions.

When the Warsaw Pact troops invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968, the liberal atmosphere of “melting” and the possibility of receiving impulses from Western art ended. Since what the regime offered could not truly sustain life, Karlíková signed the document Charter 77 in 1977, criticising the political power and the power of the state. A career as an official artist suddenly became entirely impossible for her. Her work thus remained in the underground until the 1990s, but she also participated in several unofficial exhibitions. The political dimension of her thinking is also evident in her reflections on the approach to nature, which she dealt with in her works. She approached ecological issues through a political sense, not only aesthetically. “‘The assumption that man can do anything, that he can adapt to anything, that technology overcomes all obstacles and finds solutions is the most fatalistic, the most damaging of all notions that have ever been born in the human mind […] our economic system insists on the absurd assumption that natural resources are unlimited and thus freely available’, writes Al Gore, as if he knew the situation in the Czech Republic and the arrogance of our government officials. He wrote his book, Earth in the Balance: Ecology and the Human Spirit (1992), during G. Bush’s tenure. Now, as Bill Clinton’s vice president, he could be a great hope. It amazes me that this book has remained completely unnoticed in our media,” Karlíková remarked critically in an interview in 199611.

Karlíková was active at a time when ethical issues pertaining to the relationship with nature, as well as with the human body, began shaping their discourse. Věra Jirousová, a critic and an art historian, organized a poll There is no such thing as women’s art on the pages of the Fine Arts magazine. Karlíková says, “I think that a woman can be as free as a man in her work. It is about her social freedom. If she has a family and children to whom she wants to dedicate herself, at least her time must be divided. In some ways, this is certainly limiting, but it can also offer an opening of an area of understanding and bring forward a different experience. I would say that it is not possible to generalise these questions. These things are too individual — a question of responsibility, emotional ties, mentality and choice, etc.”12 She further elaborates on her attitude: “But, of course, that man and woman are completely different beings, even at the first sight. However, I would not differentiate their approach to art. When it comes to the perspective one has of the world, the two areas intersect. Perhaps a woman’s approach to the world is often more positive, while the negative phenomena are also felt more profoundly. She can laugh at life, but she can rarely make fun of it. The difference between the two anatomically and biologically different beings gradually disappears in personal history if they can touch the deepest layers in their pursuit of the essential, which in happy moments (I do not mean happiness as such) come unexpectedly. We do not know how they have appeared here and therefore they are rare. And here both of them are just equally amazed.”13

The text was prepared by Eva Skopalová (2021).

1Johana Lomová, Textile works of Olga Karlíkové, [in:] Emma Hanzlíková, Markéta Vinglerová (eds), "Pocta suknu", Humpolec, 2018, s. 223.2Ibidem, s. 225.

3Image: Olga Karlíková, Carpet, 1959, Moravian Gallery in Brno.

4Image: Olga Karlíková, Decorative fabric, 1960, Moravian Gallery in Brno.

5Miroslava Hlaváčková, Olga Karlíková, Galerie Benedikta Rejta, Louny, 2011 s. 11.

6Jiří Zemánek, Interview with Olga Karlíková, [in:] "Atelier", č. 2, 1996, s. 7.

7Image: Olga Karlíková, The voice of a Rooster and a Turkey, 2004, source: https://agosto-foundation.org/gallery/olga-karlikova.

8Image: Olga Karlíková, Whale Singing, 1988, oil on hardboard, 56 x 75 cm, source: https://www.artlist.cz/dila/zpev-velryby-5788/.

9Miroslava Hlaváčková, Olga Karlíková (Louny: Gallery of Benedikt Rejt, 2011) s. 7.

10Image: Olga Karlíková, Water III, 1980-1989, oil on canvas, 47 x 55 cm, source https://www.artlist.cz/dila/voda-iii-5789/.

11Jiří Zemánek, Interview with Olga Karlíková, [in:] "Atelier", 1996(2), s. 7.

12Věra Jirousová, There is no female art, [in:] Art Education, 1993(1), s. 51.

13Ibidem.

– narodila se v roce 1923, zemřela v roce 2004 – byla česká malířka a textilní umělkyně. V roce 1948 vystudovala Vysokou školu uměleckoprůmyslovou, diplomovala v ateliéru textilní tvorby Antonína Kybala. Po absolutoriu pracovala v Ústavu bytové a oděvní kultury, kde vytvářela nejen abstraktní vzory textilií. Od šedesátých let se začala věnovat vlastní volné umělecké tvorbě.

Olga Karlíková pocházela z obchodnické rodiny, otec Leopold Karlík vlastnil mezinárodní plavební společnost Karlík a spol., avšak její cesta k umění nebyla až tak dlouhá. Byla vnučkou Antonína Zajíčka, stavitele, který navrhl několik kroměřížských domů. Na uměleckou scénu vstoupila po absolvování francouzského lycea v Praze, a to díky nástupu na grafickou školu Officina Pragensis (1939-1940). Válečná léta druhé světové války strávila v ateliéru Antonína Strnadela na Uměleckoprůmyslové škole (1942-1945), která po skončení války získala statut vysoké školy a Karlíková zde dále pokračovala v ateliéru textilní tvorby pod vedením Antonína Kybala (1945-1948). Kybalův ateliér pro Karlíkovou byl patrně cestou k volnému umění – a to i přes to, že se jednalo o ateliér užité tvorby. A snad právě zde se Karlíkové otevřela cesta k minimalistickým liniím, k nímž dospěla ve svých kresbách. V 50. a 60. letech pracovala v Textilní tvorbě, respektive později Ústavu bytové a oděvní kultury. Svou vlastní práci představila na výstavě v roce 1959 v Galerii Československého spisovatele.

Textilní tvorba v 50. a 60. letech byla jednou ze svobodných míst umění, kam pronikaly tehdejší abstrahující tendence volného umění ze Západu. Umělci tak měli příležitost v rámci užitého umění uniknout vynucenému realismu tehdejší politické ideologie. Nakonec to byla i vlastní technologie nových materiálů, která vycházela vstříc novým způsobům dekoru, jelikož nové tkaniny s neznatelnou strukturou vazby skutečně potřebovaly další zpracování. Abstraktní vzory se tak staly vhodným doplněním, jelikož nepracovaly s jedním souvislým vzorem, ale skvrnami, které bylo možné svobodněji užívat v ploše. Karlíková ve svých návrzích textilií právě pracovala s touto abstraktní expresivitou, ačkoli ve volné tvorbě se stále uchylovala k zobrazivému pojetí Václava Bartovského, který v ÚBOKu vedl kurz malby1. Johana Lomová však upozorňuje na to, že označit textilní návrhy jako autorské gesto Olgy Karlíkové je problematické, vzhledem ke způsobu fungování ÚBOKu, se tak jednalo spíše o kolektivní práci, jejíž vliv se projevil ve výsledných detailech jako je třeba barevné ladění textilie234.

Karlíková se začala věnovat vlastní volné tvorbě postupně, nejdříve po práci a v neděli. Poté s kroužkem studentů v okruhu Václava Bartovského jezdila malovat do plenéru v okolí Litoměřic5, až se do vlastních obrazů zcela ponořila. Karlíková se postupně odkláněla od krajinomalby a začala vytvářet první frotáže, ale ačkoliv na začátku 60. let krajinu v tradičním slova smyslu opustila byla jí nástrojem pro úvahy o tvaru a prostoru. Zájem Karlíkové o přírodu se tak z jejího díla nikdy nevytratil, naopak zůstal v jejím uvažování neustále přítomný. „Strom je živý organismus pevně spjatý se zemí. Jeho vlastní pohyb se děje uvnitř. Je neviditelný, ale tušíme jeho sílu. Strom roste a mohutní, chvěje se a ohýbá ve větru. Žije v symbióze s ptáky. Jeho koruna je protkána jejich letem: je jejich útočištěm, některé živí, oni zase roznášejí jeho semena daleko do okolí. Stromy se dožívají nejdelšího věku ze všech živých organismů, raději bych řekla bytostí. Jsou zranitelné, křehké a bezbranné, ale i houževnaté. Staré lípy v aleji, kterou pokáceli a pařezy zlikvidovali frézou, druhý rok obrazily z kořenů. Stromy mají své příběhy, často velice smutné. Vracím se k některým ve svém okolí, někdy po delší době, kdy jsem se potulovala a prožívala své zmatky. Jsou tu na svém místě, některé zle poraněny, s odumírajícími větvemi, ale s rašícími pupeny, zlátnoucím listím nebo holými korunami. Stromy mne přesvědčují o řádu přírody. Je to veliké téma, nevím, jestli na to stačím.“6

Nakonec se strukturální abstrakce Karlíkové přiklonila k akustice přírody, zaznamenávala totiž zvuky ptáků7, žab a podle záznamu také velryb8. Její práce se tak začala pohybovat mezi textovým záznamem, notací a vizuálním znakem. Její vizuální partitury přírody měly blízko ke kaligrafickým básním v asijském umění, na které explicitně způsobem adjustace odkazovala. Své svébytné pojetí jednou popsala: „Co je báseň, co je poezie. Snad záblesk světla, pohled ostrý a zároveň křehký, zjevující tajemství, nořící se do propastných hlubin, vznášející se do závratných výšek. Několik slov, linek nebo skvrn odhalí často víc než mnoho mluvení.“9 Původní zájem o krajinomalbu se tak abstrahoval do studia rytmů vodní hladiny10, prostor s poryvy větru a další podobných abstrakcí.

Když v roce 1968 vstoupily vojska Varšavské smlouvy do Československa, liberální atmosféra „tání“ a možnosti přejímání impulzů z umění Západu skončila. Z neudržitelnosti tehdejšího režimu pro život Karlíková v roce 1977 podepsala dokument Charta 77, kritizující politickou i státní moc, a její dráha oficiální umělkyně pro ni byla zcela znemožněna. Její tvorba tak zůstala v undergroundu až do devadesátých let, ale účastnila se i několika neoficiálních výstav. Politický rozměr jejího uvažování je patrný i v úvahách o přístupu k přírodě, kterou se zabývala ve svých dílech, k ekologickým otázkám tak přistupovala přirozeně politicky, nikoli jen esteticky. „ ,Domněnka, že člověk může vše, že se může přizpůsobit čemukoliv, že technologie překoná všechny překážky a nalezne řešení, je nejosudnější, nejškodlivější ze všech, které se kdy zrodily v lidské mysli […] náš ekonomický systém trvá na absurdním předpokladu, že přírodní bohatství je ničím neomezené a volně dostupné,‘ píše Al Gore, jako by znal situaci v České republice a aroganci našich vládních činitelů. Svou knihu Země na misce vah psal ve funkčním období G. Bushe. Nyní jako viceprezident Billa Clintona by mohl být velkou nadějí. Udivuje mne, že tato kniha zůstala v našich médiích celkem nepovšimnuta,“ poznamenala kriticky Karlíková v rozhovoru v roce 199611.

Karlíková působila v době, kdy etické otázky vztahu k přírodě, stejně jako lidskému tělu teprve formovaly svůj diskurz. Věra Jirousová, kritička a historička výtvarného umění, uspořádala na stránkách časopisu Výtvarné umění anketu Žádné ženské umění neexistuje. Karlíková říká, „myslím, že ve své práci může být žena stejně svobodná jako muž. Jinak je to s její sociální svobodou. Pokud má rodinu, děti, kterým se chce věnovat, musí přinejmenším svůj čas dělit. Nějakým způsobem je tím jistě omezena, ale zároveň se jí možná otevírá oblast porozumění a jiná zkušenost. Řekla bych, že není možné tyhle otázky zobecňovat. Jsou to věci příliš individuální – otázka odpovědnosti, citových vazeb, mentality i volby atd.“12 Svůj postoj však dále rozvádí: „Ale ovšem že muž a žena jsou zcela odlišné bytosti, už od pohledu. Přístup k výtvarné práci bych však u nich nerozlišovala. Co se týče pohledu na svět, obě oblasti se prolínají. Snad je ženský přístup k světu častěji pozitivní, záporné jevy žena cítí bolestněji, životu se dokáže smát, ale zřídkakdy vysmívat. Rozlišnost obou anatomicky a biologicky odlišných bytostí v osobní historii postupně mizí, dokáží-li se v hledání podstatného dotknout nejhlubších vrstev, které ve šťastných okamžicích (tím nemyslím štěstí jako takové) přicházejí nečekaně, nevíme odkud, a proto jsou vzácné. A tu jsou oba už jen bytostmi stejně žasnoucími.“13

Text připravila Eva Skopalová (2021).

1Johana Lomová, Textilní práce Olgy Karlíkové, [v:] Emma Hanzlíková, Markéta Vinglerová (eds.), "Pocta suknu", Nadační fond 8smička, Humpolec, 2018, s. 223.2Ibidem, s. 225.

3Obrázek: Olga Karlíková, Koberec, 1959, Moravská galerie v Brně.

4Obrázek: Olga Karlíková, Dekorační tkanina, 1960, Moravská galerie v Brně.

5Miroslava Hlaváčková, Olga Karlíková (Louny: Galerie Benedikta Rejta, 2011) s. 11.

6Jiří Zemánek, Rozhovor s Olgou Karlíkovou, [v:] "Atelier", č. 2, 1996, s. 7.

7Obrázek: Olga Karlíková, Hlas kohouta a krocana, 2004, zdroj: https://agosto-foundation.org/gallery/olga-karlikova.

8Obrázek: Olga Karlíková, Zpěv velryby, 1988, olej na sololitu, 56 x 75 cm, zdroj: https://www.artlist.cz/dila/zpev-velryby-5788/.

9Miroslava Hlaváčková, Olga Karlíková, Galerie Benedikta Rejta, Louny, 2011, s. 7.

10Obrázek: Olga Karlíková, Voda III, 1980-1989, olej na plátně, 47 x 55 cm, zdroj: https://www.artlist.cz/dila/voda-iii-5789/.

11Jiří Zemánek, Rozhovor s Olgou Karlíkovou,[v:] "Atelier", 1996(2), s. 7.

12Věra Jirousová, Žádné ženské umění neexistuje, Výtvarná výchova, 1993(1), s. 51.

13Ibidem.