Magdalena Moskwa

– born in 1967 in Poddębice. She studied at the Wł. Strzemiński State Higher School of Visual Arts in Łódź at the Faculty of Textile and Clothing. She does painting, sculpture, photography, embroidery, and creates non-utilitarian objects-clothes. Her works are dominated by female figures and motifs of the human body shown in fragments. The main themes of her paintings and spatial objects are carnality and spirituality, rites of passage and death. The artist’s works can be found in the collections of, among others: Museum of Art in Lodz, Zachęta National Gallery of Art or Municipal Gallery of Art in Lodz. In 2020, she received the Jan Cybis Award.

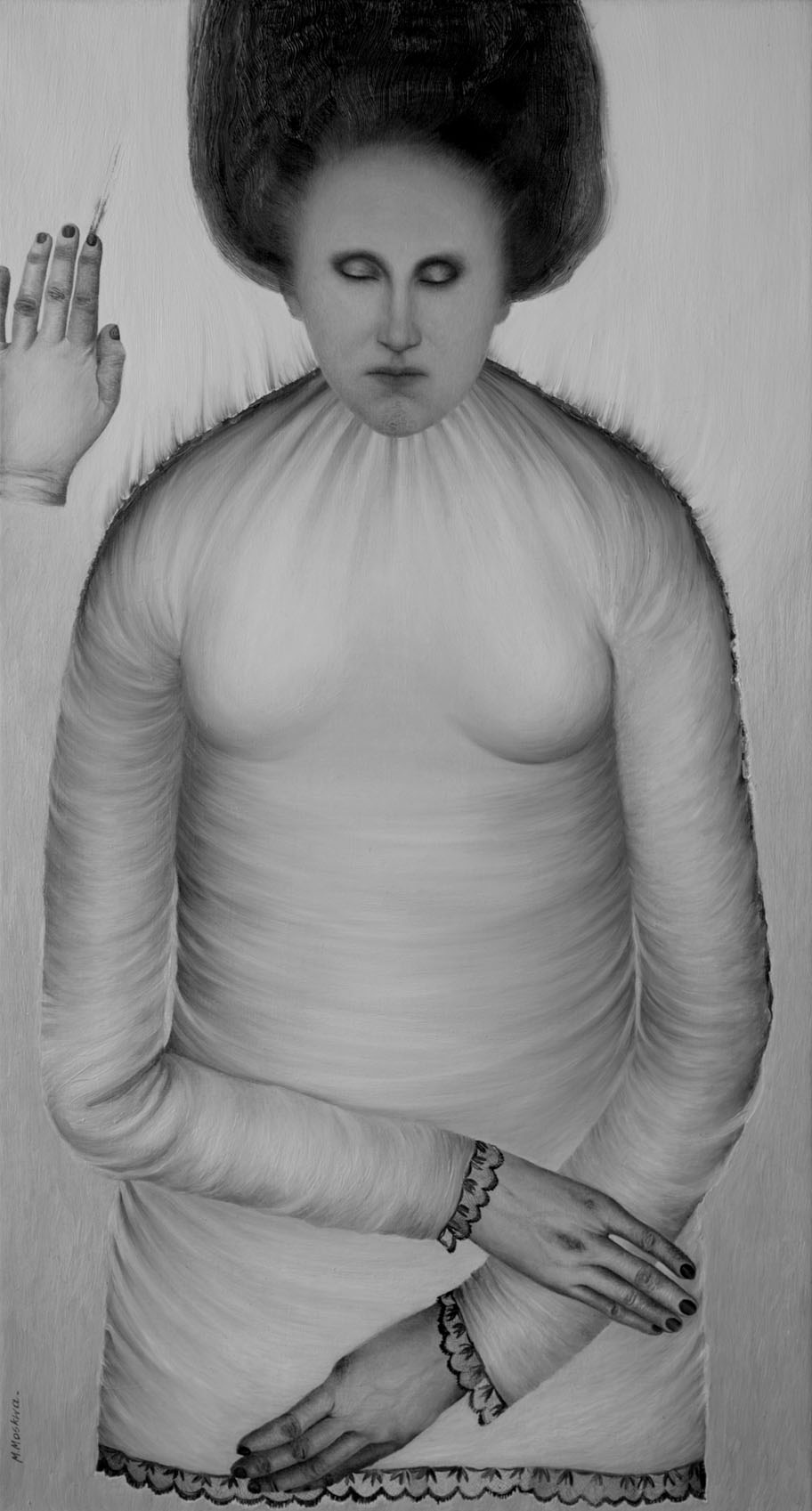

The most important theme of my creative explorations is a psychologically enhanced portrait. In painting, I started from the image of a person who was an embodiment of the psychological layer, of emotional states. Earlier works on canvas are quite close to “classical” portraits1 with a centrally located figure. However, it is not about being faithful to the facial features, but about extracting the essence and energy. They are physiognomies assembled from the appearances of various people, including my own, which are the embodiment of inner states. The images are not realistic, but they are striking in their verisimilitude of representation, known for example from coffin portraits, in which I am fascinated by the energy of an enchanted life captured in the image. From my earliest works, I aim for the image to be perceived as a living presence and to emanate power. Sometimes I place prepared remains (teeth, small organs or hair, like relics in a reliquary) as a tool for making a person present in the image. Just as the heart of a reliquary are relics and the energy flowing from them, so the heart of a painting is its essence, that is, the intentions and the message that the artist contains in the painting. The form of a painting is the materialisation of this energy, and the painting itself is a plane of exchange of thoughts and energy between the artist and the viewer.

In 2004 I replaced the canvas underpainting with a chalk mortar on a board which allows me to create a relief on the surface in order to give the illusion of pulsation, softness, warmth of the body and to penetrate deep into the painting. In this way, “images of corporeality” are created which convey the delicacy of the matter of which we are made and its peculiar beauty. In subsequent relief-shaped paintings, the skin layer is at the same time the layer of the painting work, which makes the represented object and the medium virtually identical2.

In later works, the painting layer is gradually slimmed down and the relief shaping of the canvas intensifies, which brings me to full sculpture, the surface of which is often completely devoid of paint, and the sculpturally shaped mortar looks like bare bone. The path through the body guides virtually all my work. It runs from the seemingly insignificant scratching of the depicted body or face in the early paintings3, through the close-up of the skin surface, the penetration of holes and the change of scale of the detail, all the way under the skin and even somewhere deeper. At some point, in this process of getting closer to the human being, I began to penetrate organic tissue close to formless matter. And this is where a very important thing happened, namely this maximum closeness and the related penetration of detail made everything even more intimate, but also more general and universal. Gone is the image in the sense of a portrait – the appearance of a figure – the face, which is always associated with a particular person. So, gone are the individual human cases, and what has appeared is the most essential thing, the impression of an organic presence.

My painting is often associated with turpism. This is probably due to the fact that I am preoccupied with beauty, difficult and not obvious, which I look for where it seems to be absent. I try to see it and share it with others through my paintings. In fact, in all my work I try to transform what is considered repulsive into something that makes you look at yourself and even admire it. This is not an imagined or added beauty, it actually exists. It is enough to forget that the viscera are repulsive to see their true, disturbing beauty. The paintings are therefore an attempt to “disenchant” the dark recesses of corporeality, which lure with their perverse beauty, make us look at ourselves and become accustomed to the reality of the body and life. Based on the human tendency to empathic reception of images, I want to bring about a situation in which the viewer begins to perceive the image with their own body on the basis of bodily co-feeling. I want the viewer, looking at these images, to identify himself and feel his body, its pulsating presence, ask himself about its sense and its end.

Confronting earthly tribulations, the awareness of the fragility and inevitability of the death of the body, fear, disgust and loneliness, I keep trying to show that life itself is beautiful, beautiful down to the blood. The exhibition Life is Extremely Beautiful was a summary of these reflections, and the title of this exhibition probably best reflects the idea that has guided my research so far.

Text created in collaboration with Karolina Maria Rojek (2020).

1Image: Magdalena Moskwa, untitled, 2002, oil on canvas., 55 x 46 cm. Courtesy of the artist.2Image: Magdalena Moskwa, untitled, 2014, relief in chalk mortar, oil on board, 24 x 32cm, collection of Zachęta – National Gallery of Art, Warsaw. Courtesy of the artist and Zachęta – National Gallery of Art.

3Image: Magdalena Moskwa, untitled, 2003, oil on canvas, 92 x 50 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

– urodzona w 1967, Poddębice. Studiowała w PWSSP im. Wł. Strzemińskiego w Łodzi na Wydziale Tkaniny i Ubioru. Zajmuje się malarstwem, rzeźbą, fotografią, haftem, tworzy obiekty–ubrania o nieużytkowym charakterze. W jej pracach dominują postacie kobiet oraz motywy ciała ludzkiego ukazanego we fragmentach. Głównym tematem obrazów i obiektów przestrzennych malarki jest cielesność i duchowość, rytuały przejścia oraz śmierć. Prace artystki znajdują się w kolekcjach m.in.: Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi, Zachęty Narodowej Galerii Sztuki czy Miejskiej Galerii Sztuki w Łodzi. W 2020 otrzymała nagrodę im. Jana Cybisa.

Najważniejszym tematem moich twórczych poszukiwań jest pogłębiony psychologicznie portret1. W malarstwie wyszłam od wizerunku człowieka, który był ucieleśnieniem warstwy psychicznej, stanów emocjonalnych. Wcześniejsze prace na płótnie dość bliskie są “klasycznym” portretowym wizerunkom z centralnie usytuowaną postacią. Nie chodzi w nich jednak o wierność w oddaniu rysów twarzy, lecz o wydobycie esencji i energii. Są to fizjonomie poskładane z wyglądów różnych osób, w tym mojego własnego, będące ucieleśnieniami wewnętrznych stanów. Wizerunki nie są realistyczne,ale uderzają weryzmem przedstawienia, znanym np. z portretów trumiennych, w których fascynuje mnie energia zaklętego, zatrzymanego w obrazie życia. Od najwcześniejszych prac dążę do tego, żeby wizerunek postrzegany był jako żywa obecność i emanował mocą. Zdarza się, że jako narzędzie uobecniania człowieka w obrazie umieszczam w nim spreparowane szczątki (zęby, drobne organy lub włosy, niczym relikwie w relikwiarzu).Poszukiwania w tym obszarze zaprowadziły mnie do refleksji,że sam obraz jest formą “relikwiarza”. Tak jak sercem relikwiarza są relikwie i energia z nich płynąca, tak sercem obrazu jest jego istota, czyli intencje oraz przekaz, które artysta zawiera w obrazie. Forma obrazu jest materializacją tej energii, a sam obraz płaszczyzną wymiany myśli i energii pomiędzy artysta i odbiorcą .

W 2004 roku podobrazie płócienne zastąpiłam zaprawą kredową na desce, która umożliwia mi reliefowe opracowanie powierzchni w celu oddania iluzji pulsowania, miękkości, ciepła ciała, penetrację w głąb obrazu. W ten sposób powstają “obrazy cielesności” oddające delikatność materii, z której zostaliśmy stworzeni i jej osobliwe piękno2.

W kolejnych ukształtowanych reliefowo obrazach powłoka skórna stanowi jednocześnie powłokę pracy malarskiej, co sprawia, że przedstawiany obiekt i nośnik stają się właściwie tożsame. W późniejszych obiektach warstwa malarska jest stopniowo odchudzana, a reliefowe ukształtowanie podobrazia wzmaga się, co doprowadza mnie do pełnej rzeźby, której powierzchnia często zupełnie pozbawiona jest malatury, a rzeźbiarsko ukształtowana zaprawa wygląda jak naga kość .Droga przez ciało prowadzi właściwie całą moją twórczość. Biegnie ona od pozornie nieistotnego draśnięcia przedstawionego ciała lub lica we wczesnych obrazach3, przez zbliżenie do powierzchni skóry penetrację otworów i zmianę skali detalu, aż pod skórę i nawet gdzieś głębiej.W pewnym momencie,w tym procesie przybliżania się do człowieka, zaczęłam wnikać w organiczną tkankę bliską bezkształtnej materii. I tu wydarzyło się coś bardzo istotnego, a mianowicie to maksymalne zbliżenie i związane z nim wniknięcie w szczegół sprawiło, że wszystko stało się jeszcze bardziej intymne, ale też zarazem ogólne i uniwersalne. Zniknął wizerunek w sensie portretu -wyglądu postaci – twarzy, która zawsze kojarzy się z konkretnym człowiekiem. A więc zniknęły, jednostkowe przypadki ludzkie, a pojawiło się to, co najbardziej istotne, wrażenie organicznej obecności.

Moje malarstwo często kojarzone jest z turpizmem. Wynika to prawdopodobnie z tego, że zajmuje mnie piękno, trudne i nieoczywiste,którego szukam tam, gdzie wydaje się być nieobecne. Ja je próbuję dostrzec i dzielę się nim z innymi poprzez swoje obrazy. Właściwie w całej twórczości próbuję przemienić to, co przyjęte jest za odpychające w coś takiego, co każe na siebie patrzeć, a nawet się tym zachwycić. Nie jest to piękno wymyślone czy dodane, ono faktycznie istnieje. Wystarczy zapomnieć, że wnętrzności są odrażające, żeby zobaczyć ich prawdziwą, niepokojącą urodę. Obrazy są więc próbą „odczarowania” mrocznych zakamarków cielesności, które nęcą swoją perwersyjną urodą, każą na siebie patrzeć i oswajać się z rzeczywistością ciała i życia. Bazując na skłonności człowieka do empatycznego odbioru wizerunków, chcę doprowadzić do sytuacji, w której widz zacznie odbierać obraz swoim ciałem na zasadzie cielesnego współodczuwania. Chcę, żeby oglądający patrząc na te obrazy zidentyfikował się i odczuł swoje ciało, jego pulsującą obecność, zadał sobie pytanie o jego sens i o jego kres .

Konfrontując się z ziemskimi utrapieniami, świadomością kruchości i nieuniknionej śmierci ciała, lękiem, odrazą i osamotnieniem, cały czas próbuję pokazać, że życie samo w sobie jest piękne, piękne aż do krwi . Podsumowaniem tych rozważań była wystawa Życie jest ekstremalnie piękne, a tytuł tej wystawy chyba najlepiej oddaje ideę jaka przyświecała moim dotychczasowym poszukiwaniom.

Tekst powstał we współpracy z Karoliną Marią Rojek (2020).

1Zdjęcie: Magdalena Moskwa, bez tytułu, 2002, olej na płótnie, 55 x 46 cm. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.2Zdjęcie: Magdalena Moskwa, bez tytułu, 2014, relief w zaprawie kredowej, olej na desce, 24 x 32 cm, kolekcja Zachęty – Narodowej Galerii Sztuki, Warszawa. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki i Zachęty – Narodowej Galerii Sztuki.

3Zdjęcie: Magdalena Moskwa, bez tytułu, 2003, olej na płótnie, 92 x 50 cm. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.